Gaby's biography was highly influenced by the Samoza dictatorship in Nicaragua. I Foto: Jugendpresse Deutschland/Gaby Baca Vaughan

politikorange: Why did you become an activist?

Gaby: To answer that question, you need to know that I grew up during a revolution. I remember the time of the Somoza dictatorship. I grew up with all these difficulties behind me. I saw with my own eyes all the fights in my region. I am from Managua, but during that time I lived in a little town. There you find a lot of trees and animals. So I grew up in very political times with many guns around me. But there was also a lot of nature. That’s why all my messages are about human rights and politics but also about nature. My personal life reflects in there. My music was influenced by all that years.

politikorange: Can you tell me more about your experiences during the revolution?

Gaby: When I was seven years old Anastasio Somoza was the president of Nicaragua. At this point, his family had ruled Nicaragua for 54 years. I was just a small kid when I heared the adults talking about freedom and revolution and all that kind of things. People who visited my family talked about Somoza being not good. They always had to whisper because it was very dangerous to criticize the president. They wanted a different Nicaragua. I grew up with that feeling. In 1979 when I was 10 years old the revolution became reality. I remeber all the people meeting at the „Plaze de la revolucion“ crying. We celebrated that day. Somoza had disappeared, and we were free. When I was 15 years old, I went to the mountains and helped cutting coffee. It was the time of the war against the „contras,“ the counter-revolutionary guerillatroop of Somozas former national guard. I always had a gun in my bag to protect myself. I grew up very fast. I learned many hard things but also many great things. I learned things about love and things about war.

politikorange: What do you fight for exactly?

Gaby: I fight for nature, women rights, human rights, against social problems and for more diversity. For LGBTQIA. I am a lesbian myself. This is a very important topic for Central America. We have still a lot to do there. When I lived in Honduras, I discovered feminism and started to work more in this field with my music. I have already told you, I grew up during a revolution in Nicaragua. As a young women I was unionised in the student movement. That wasn’t always easy. Many men there were really macho and discriminatory. I felt that I had to free myself from things like that and become who I want to be. When the revolution was over, I went to Honduras and Guatemala. There I met many powerwomen doing feminist work. They became my real family and I discovered that feminism was my fight.

I fight for nature, women rights, human rights, against social problems and for more diversity.

politikorange: When did you start making music?

Gaby: I started to play the guitar when I was 12 years old. When I was 22 or 23 years old I wrote my first song. During that time I discovered the power of music, that it can be used to empower people. I did communication studies at the university. Music can be used for communication. So I didn’t study music but it had always been my passion. I grew up surrounded by lots of music and poetry. Nicaragua is rich in that too.

politikorange: How do you combine music and protest?

Gaby: I have different tools to transport my message in music. I try really hard to be part of the subculture here in Nicaragua. One way to do so is rap music. It’s funny because all the rappers are really young and I am already 50 years old. But with hip hop and rap music I reach young people. Hip hop is also very macho. So I go to the center of the problem and make feminist rap music. Another tool I use in my music is humor. With humor you can connect many different people. The young ones, the old ones. Everyone.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rtUU1POXMaw

politikorange: Which song of your work is your favourite?

Gaby: I think it’s „Chocoyito.“ The song speaks about freedom. A „chokoyito“ is a little parrot here in Nicaragua. They live in vulcanos. They are very noisy exactly like the Nicaraguan people. The problem is that people here hunt them down to sell them later. I don’t like that. So this song is about freedom. When you are born as „chokoyito,“ as a bird, you need to fly. And it’s also your right to fly. With humans it’s the same. We are like birds, we need to fly to be happy. Here in my country we don’t have the freedom to sing and fly. That’s why I really like this song.

politikorange: Does the COVID-19 pandemia affect your work?

Gaby: Yes, this situation is global. A lot of my work takes place in the streets. I go out and play with the people, with the feminists, but now this is impossible because of COVID. Right now a lot of people I know who are making arts are connecting to find a way to continue working. It knew that it was not going to be easy when I decided to quit my job in advertising and started to make my living on music . But now it’s even harder. It have been many years since I’ve stopped working in an office, getting a salary. So I got the feeling we will make it. We will find a new path. That’s why I am really happy to work with so many young people. The young people have the key to the future. They will know what’s the next step. I learn a lot from them.

politikorange: All around the globe, the right to free assembly has been restricted. That also means it’s not possible to demonstrate. People have to become creative now. Do you think now is the time art will change the world?

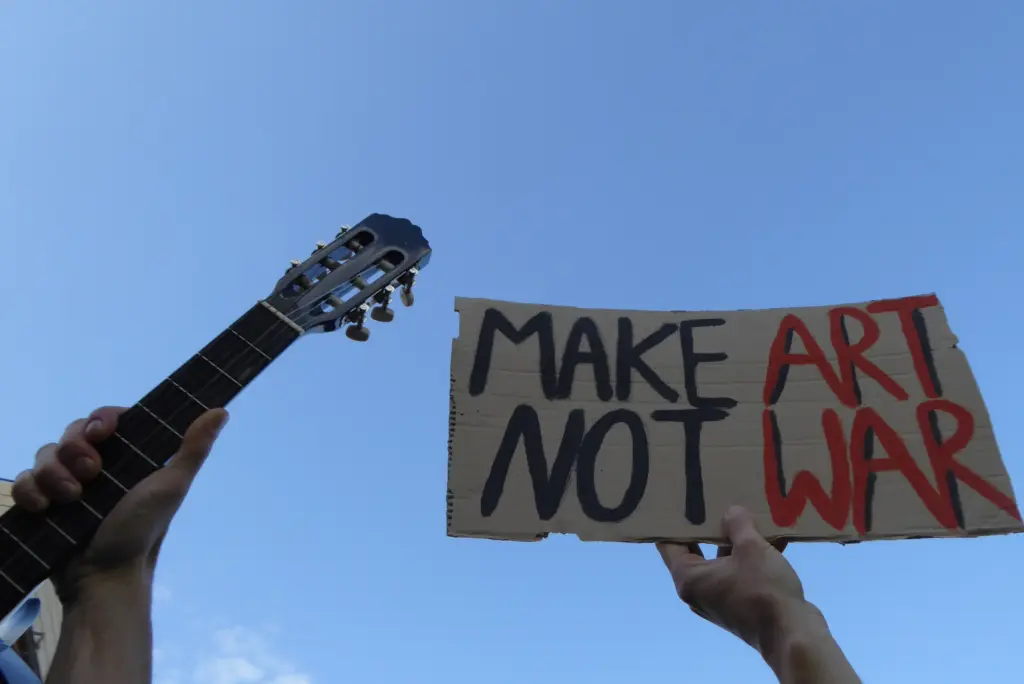

Gaby: Yes, now is the time. I think art is powerful. Art is the voice of the people who can’t speak. That’s why it is very important. Once someone close to the government called me and told me I have to be quiet if I want to stay alive. I answered: „I need to sing to be alive. That’s all I do, singing.“ He laughed. It’s true I am like a bird – if I don’t sing I can’t live. If you don’t sing about the right things, you don’t make art, you are just entertainment. You become part of the problem. We need to put art in the right places, because the world has to change now. Art is one of the best tools to do so.

If you don’t sing about the right things, you don’t make art, you are just entertainment. You become part of the problem. Gaby Baca Vaughan

politikorange: Is art always protest?

Gaby: Yes, art is protest, but apart from that art has more to do. Art has to propose new solutions. We need art with a message, that does more than impeaching what’s going wrong.

Gaby performed live at the Eine-Welt-Landeskonferenz 2020 – watch her performance here!

ABOUT: GABY BACA VAUGHAN

Gaby Baca Vaughan was born in 1969 in Managua, Nicaragua. As a child she witnessed the end of the Samoza-dictatorship and the revolution of 1979. In 1984 she became part of the Sandinista Youth and the student movement. In 1990 she started studying communication studies in Mangua. In 1996 she recorded her first song „Sirenas" in Costa Rica. In 1997 Gabriela moved to Honduras and had first contacts with other feminists. In 2005 she decided to stop working in advertising and work exclusivly on her project LaBacaLoca.

Since then she has publish two albums and is working on two more.

Empfohlene Beiträge

Fishing for women’s rights? So wollen die Parteien für Gleichberechtigung sorgen

Felicitas Nagler