Today’s society knows what LGBTQI+ means, but do we know how societies in other countries deal with it? In Germany and Ukraine, the definitions seem to be very different, starting with the fact that in Ukraine the letters only reach to LGBT. A comment by Anastasia Kuznietsova and Daria Kisieieva – two Ukrainian young journalists – about different notions in both countries.

LGBTQI+ life in Ukraine The queer community doesn’t have an easy life in Ukraine. Society does not have a high level of awareness. The government does not spread tolerance, so Ukrainians remain in the darkness and believe that only traditional family models are normal. That’s the reason why some pride and equality marches end in physical violence. For example, just a few minutes after the start of KievPride 2019, a column of participants was attacked by opponents of the march, and several people were injured. At the same time, it should be mentioned that more than 8.000 people participated in the 2019 Equality March, which is 3.000 more than last year. The situation in Germany nowadays is very different by comparison. The Berlin pride (Christopher Street Day) on July, 27th, 2019, has been held without attacks: the procession held posters with the slogans like „No sex with Nazis“ and „Send the patriarchy to hell“. They threw confetti and waved rainbow flags. The celebration ended in a huge party with people dancing and a concert at the Brandenburg Gate. This year’s Equality March is considered to be the largest within the last four years, with the number of participants reaching around 150.000. Sergei from Kiev, a participant of the Berlin Pride, shared his impressions: „This atmosphere of mutual love and respect inspires you to return and fight for diverse kinds of people to be more respected in our country“. LGBTQI+ in the Ukrainian media Despite our individual point of view on this topic, media sometimes tries to impose their opinion and show people what the „right way of thinking“ is supposed to be. How does Ukrainian media write about LGBTQI+ and do they cover this topic at all? It’s safe to say that there is also a huge difference in the media coverage of both countries. In March 2018, the Institute of Mass Media in Ukraine monitored eleven leading Ukrainian online media outlets that cover news about „LGBT people“. They highlighted 105 stories on LGBT topics, 63 of which were associated with scandals and media stars. About 20 percent of the stories included homophobic expressions and content manipulations, and only 10 percent had a positive background. Experts conclude that Ukrainian media writes exclusively about one point of view: mostly the opinion of opponents. Moreover, the articles are usually written with an ironic undertone. Thus, people ridicule this topic instead of rethinking it. Some examples are: „Transgender woman Daniela Vega went down in Oscar history“, and „A transgender girl defeated a man according to the rules of MMA“. It should also be taken into account that Ukrainian media space has particularized magazines for LGBTQI+ people, some hubs, and some social groups, but this is not well-known, and many people wouldn’t even believe in their existence. German journalists try to highlight situations from different points of view, and write about these topics more often. Germany has a few magazines for queer people like siegessäule.de, Straight Magazine, or L‑Mag. Additionally, the Berlin daily newspaper „Tagesspiegel“ has a special category for queer people, called „Queerspiegel.“

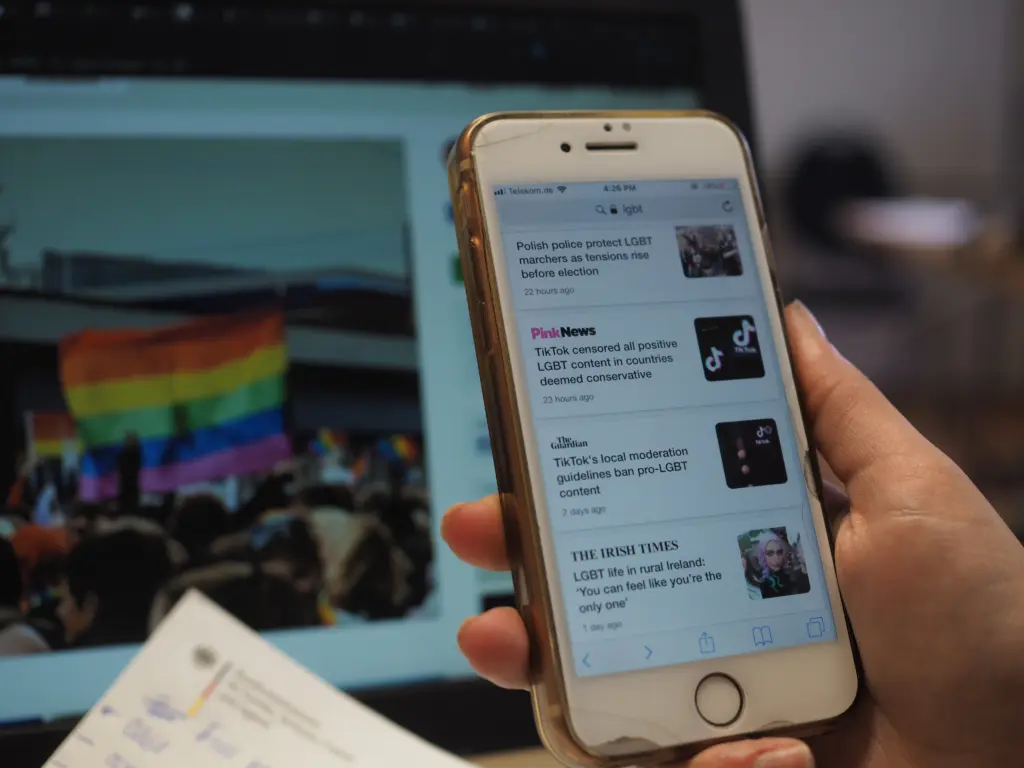

Photo: Linus Walter